Stray

Angela Huo

Shadows let loose like dogs without their leashes, spring mornings lovely and clear. Gisela Crawford is two years younger than me, baby fat still clinging to her arms and legs and cheeks, but I condescend to play with her in the schoolyard because Mrs. Crawford packs fried chicken with mayonnaise on Fridays. I ask Gisela if I can watch her eat. Gisela smiles, tosses the leftovers to me and I gnaw at bits of chicken still clinging to bone, eye to eye with dragonflies skimming low as she says good dog good dog over and over. My pride pares away. I am the youngest of six daughters in a household where attention as open as Gisela’s is rare as a double-yolked egg. Gisela stills the merry-go-round with one foot, leans against the back of the seat, and watches me eat. When summer comes around, she invites me to her house. Two stories, Victorian style. As a child, I realized I could say certain things to get people to like me, so I say to Gisela’s mom: Gee madam, you look freshly in your twenties! with the suaveness of a middle-aged businessman, and she laughs, quelling the swells of my disdain. Seeing that my slacks are short enough to bare my bony ankles, that I wear my grandfather’s threadbare sailing coat, Mrs. Crawford indulgently dresses me up in Gisela’s outgrown clothes, brushing my hair, touching me with a stranger’s hand—and I am an ocean of wanting, voracious in the way I devour her affection. With six sisters by blood and not enough food to fight for, I leave the table hungry. So it begins to happen: I sneak to their house, tap at the window. Mr. Crawford pretends not to hear, but Gisela’s mother loves when I join them for dinner; she has always wanted a second child. They don’t say anything when I pocket handfuls of meatballs and beans, stashing them under my pillow when I get home. Mr. Crawford never says he doesn’t like me, but I notice, the same way I know when Ma is drunk, when Da is trying to disappear. I notice when Gisela’s mom leaves bowls of steak on the porch for stray foxes, Mr. Crawford throws the steak away, washes the bowls, wipes them clean. He has a way of speaking. Tells it like it is. Keep feeding stray animals and they’ll expect more, he warns, and when they see you don’t love them enough—and you can’t—they bite. He looks at me. I smile, hiding small, baby teeth behind my lips. I lose my first tooth the week before Mr. Crawford quits his job and the Crawfords move north. Ginkgo leaves fall the day Gisela recites her new address to me, spinning slow circles on the merry-go-round. I seethe. The next time Ma comes home with a snootful and Da cowers in his study, head bowed, there is nowhere to go when the screaming begins. I blame the Crawfords. Do they remember? Once there was a dog that gnashed its teeth at the heavens. Ma throws a mason jar of yellow peaches at my head because I am the youngest, the most vulnerable, the most innocent and most satisfying to hurt, and I blame the Crawfords. When I run away from home I leave many things behind, catch the earliest northbound train. In the morning, I see that someone has set fresh tea next to me. Hot water can feel like ice if you stick your fingers in for long enough. I have the address memorized and I am going home, where I belong, teeth sharpened, ready to eat, until I am full.

Angela Huo is a junior in Jonathan Edwards College majoring in Statistics & Data Science.

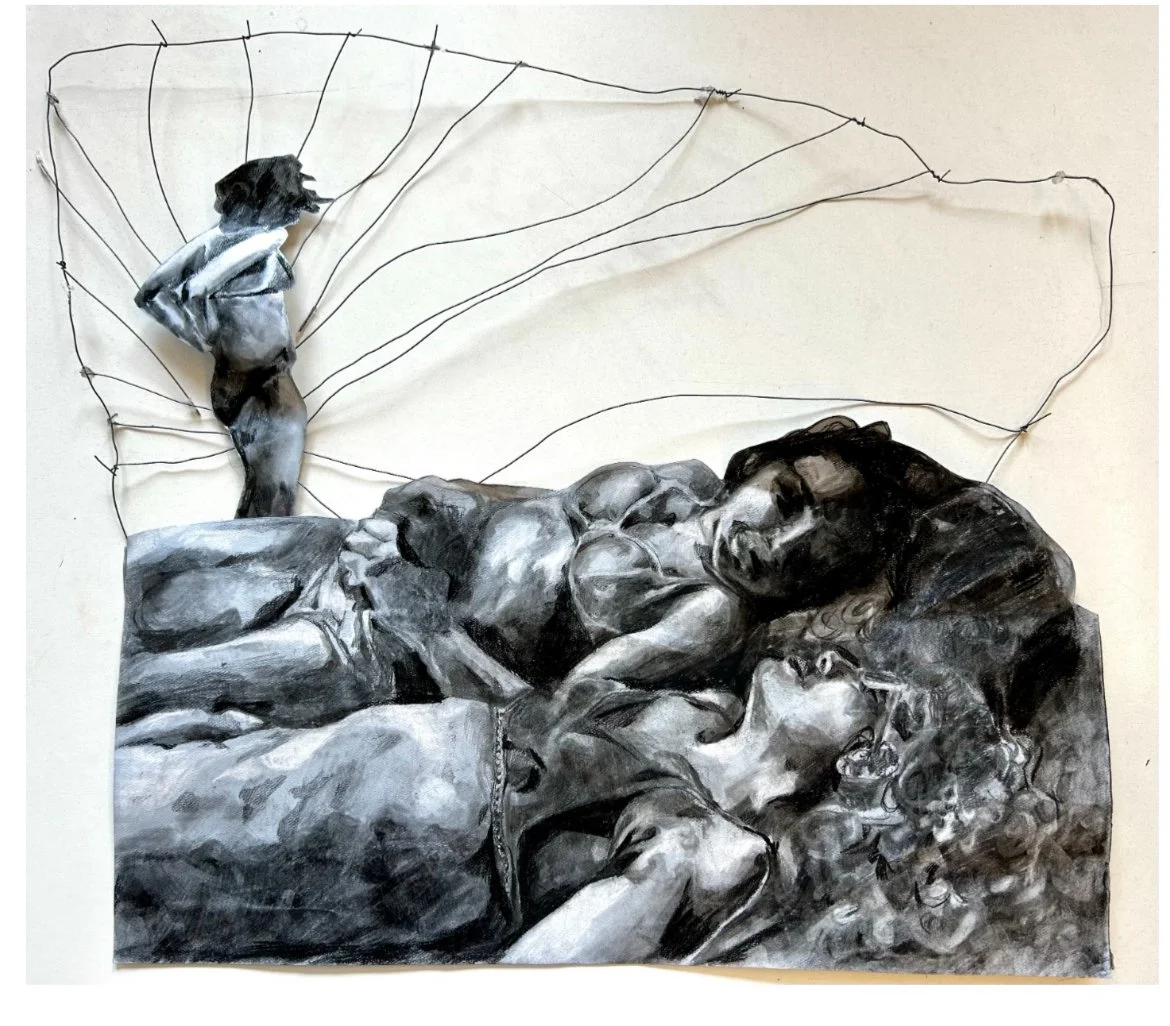

ABOUT THE ART | Threes by Madeline Hutchinson, 2025. Madeline Hutchinson is a student at Yale University.